As a photographer who learned his craft before autofocus became a truly reliable technology, my earliest challenge was focusing the lens. Those who picked up photography after the cameras could focus faster than we would ever be able to do ourselves won’t know the frustration of that particular learning curve. But focusing the lens was never so hard as learning to focus the attention of those who might read my photographs. No camera in the world can do that on our behalf.

In my capacity as a teacher, I look at a lot of photographs, many of them from younger photographers (young in craft, if not in years) who are fully capable of making pictures that are tack sharp. Yes, they are sharp, but they are also unfocused.

By far, the most common reaction I have to photographs I am asked to critique is, “I don’t know what you want me to look at.” There’s too much in the frame. There’s no clear subject. The moment is ambiguous. Everything is in focus, but nothing has impact.

The more you put in the frame (or fail to exclude), the less impact any one element has, and soon it’s a photograph that isn’t really about anything specific.

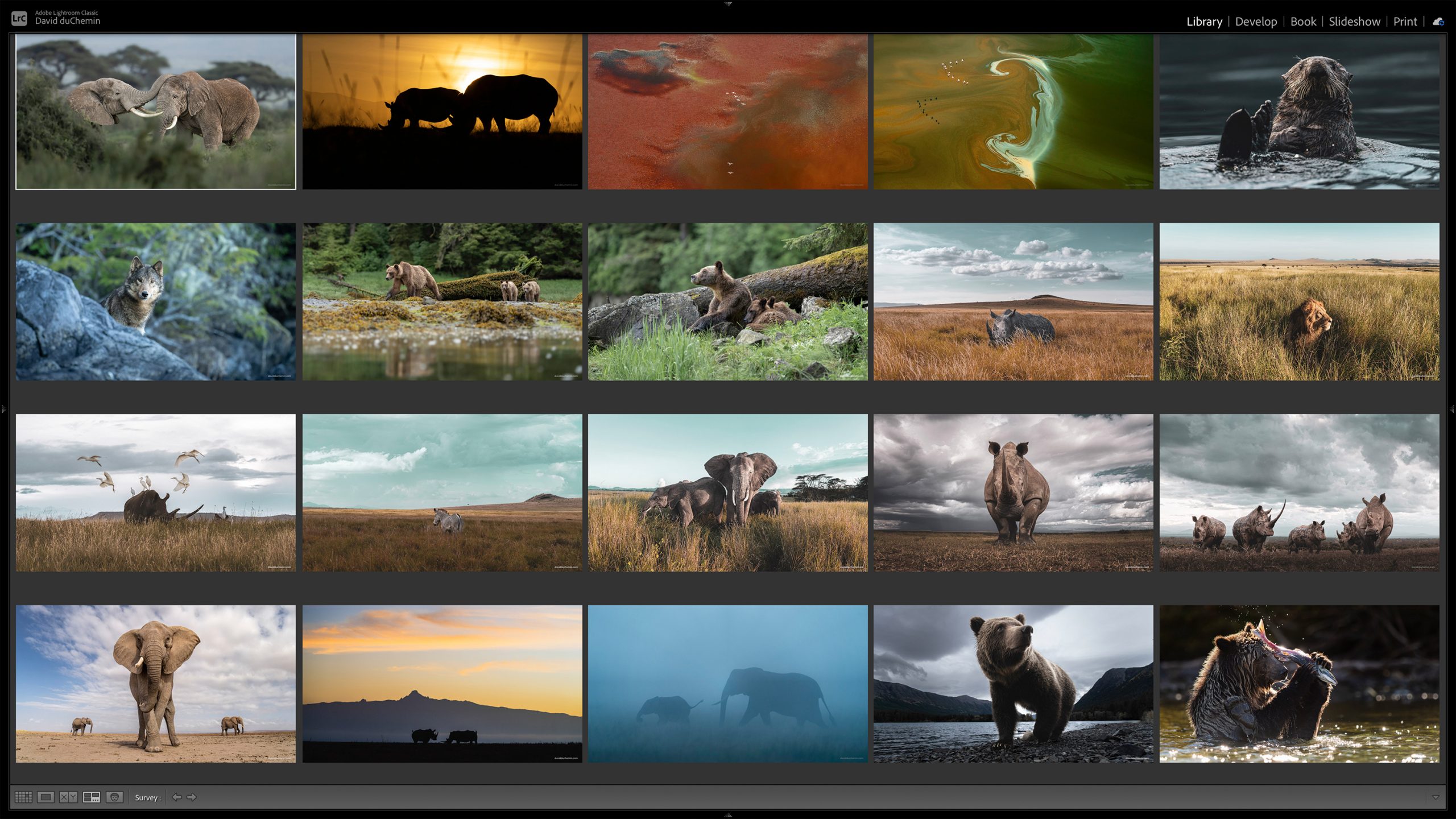

I have my own biases. Look at the images I’m including in the desktop wallpapers I’m giving you this week (keep reading, they’re at the bottom): they lean towards simplicity and compositions that isolate key elements and exclude or obscure others. They are more powerful for their simplicity because if I ask you to give your attention equally to everything in a busy frame, you will end up giving it to nothing at all because busy photographs are exhausting to read. We can only pay attention to so much.

Photography is an art of exclusion. What we leave out is as important as what we leave in because what we do not exclude dilutes the power of what we include.

When you see something you want to photograph, the instinct is to raise the camera and press the button, making focus and exposure decisions in between or letting the camera do that for you. It’s never been easier to make a photograph of something. But making a photograph about something more is just as challenging as it always was—and that begins with your thoughts. Mindfulness. Intention.

Why did you raise the camera in the first place? What type of thing did you see? (In this case, let’s pretend it was a bear.) What was it about that thing that you want to express or show me? Was it the bear in a certain light? Was it the shape of the backlit bear or the details on the face of a side-lit bear? It doesn’t have to be a bear. For Edward Weston, the challenge was to photograph a rock, have it be a rock and yet more than a rock.

It has to be more than the subject, for the subject rarely carries the photograph. I’ve seen—and made—some very unappealing photographs of some very beautiful subjects.

If the photograph says nothing more than “This is a bear (a rock, a dog, a sunset),” then it’s probably not worth looking at for very long. And it probably won’t be remembered because we already know what bears, rocks, dogs, and sunsets look like. And it probably won’t make me feel anything out of the ordinary.

As the person reading your photograph, I need you to show me more. A moment of grace. A glance. A juxtaposition or contrast. A play of colour or light. Some insight or perception. I need you to show me something about the thing you are so mesmerized by that you would go to the trouble of picking up the camera in the first place; I need you to isolate it. But you can’t do that until you know what “it” is. The picture you are assembling with the elements you choose to keep in the frame, where you put them, which lens you use, and so on—what’s it all about? Which one thing are you trying to show me? Do you really need everything in the frame to express that? Sure, your camera is focused, but are you?

What is essential? Show me that. And where you can, show me only that.

That might mean tighter framing. But it might also mean isolating with light, allowing the unimportant elements to be obscured by shadow. It might mean finding a different angle from which the extraneous is less obvious. It could mean blurring it out, more or less, with a shallow depth of field. It might mean a different lens. Slow shutter speeds and moving subjects (or moving cameras) can isolate elements while blurring others. Waiting a moment can sometimes be all it takes. Moving distractions is sometimes impossible, but moving the camera does the trick instead.

Show me more by showing me less.

I need you to simplify, and that’s not easy. Steve Jobs once observed that “Simple can be harder than complex. You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple.”

You’ve probably nailed focusing the camera, so stop worrying about that and put more effort into focusing yourself (first) and the photograph.

This question continues to guide my own efforts: how much can I remove from the frame before I lose what is essential? That does not always mean the tightest crop possible. The negative space is often essential, and removing it can destroy the feeling I’m trying to create.

Only you know what is and isn’t essential because only you know what your photograph is about. And only once you’ve removed what is inessential will I have any hope of knowing that as well.

For the Love of the Photograph,

David

New Desktop Wallpapers

It’s been a while since I gave you some desktop wallpapers. These should look great on anything up to a 4K monitor. Click this link HERE or the image above to download a zip folder of 24 wallpapers, most of them from 2024, but I’ve thrown in some favourites from the last couple of years. I hope you enjoy—and find some wonder or inspiration in them.