When people think of the Middle East, the first images that come to mind are often of conflicts, war, genocide, and pain. However, this perception is largely influenced by how the mass media chooses to portray the region. Depicting Muslims, who are people of color, in such stereotypical ways has often served as a tool for propaganda, spreading harmful narratives and fueling xenophobia. In the face of such oppression, it’s important for us, as a journalistic portal, to showcase the unseen and accurate side of the region. To achieve this, we are highlighting a decade-long collection of work by the best Middle Eastern women photographers, who capture the diverse and vibrant aspects of their native and adopted homes.

The lead image is by Norah Alamri. All images in this roundup of photographers are used with permission from the photographers in our interviews, which are all linked accordingly.

Norah Alamri

Since 2010, Norah, who lives in Saudi Arabia, has been documenting the country and its distinct culture, traditions, and food. Her images, which capture fleeting glimpses of what makes Saudi Arabia so rich, make you feel a sense of joy. Whether they are images shot inside a mosque or of a group of men enjoying music, Norah’s images dismantle the stereotypical notion the West often projects when it portrays the region.

If you look at the image above, you will see how two men, wearing their traditional attire, relaxing as the evening sets in. The picture depicts the men and their calm attire. In fact, they seem quite pleased to be chosen as the subject of the image. Photographically, the image captures everything that portrays Saudi in a positive light. The image is clearly from a market where the men sell carpets, jugs, and clothes. It proves that people in the kingdom are like humans anywhere around the world. If the region were totalitarian, then Norah would not be able to capture the men, spending some time by themselves. The cars in the back block the view, and the blown-out highlight can be distracting. However, that’s something we can ignore.

In our interview, Norah said:

For me, street portraits are very important. I like to photograph people in a way that reflects their background or the work they do, focusing on things like the way they dress, for example. Sometimes I want to capture the situation that person is in, and I make sure to support that portrait with the whole intent behind the shot, like their places or their neighborhoods – that means we end up having interesting portraits.

Follow her on Instagram.

Rania Matar

Born in Lebanon, Rania moved to the US in 1984. However, it wasn’t until the September 11, 2002 attacks that she decided to begin making images. She chose photography to help break the stereotype that was seen on news channels. “I became interested in telling a different story of the Middle East and started taking pictures in Lebanon,” she told us. Her projects, which often feature young girls (about 20), talk about the challenges and struggles that they face in their transition period from teenager to adolescence.

For instance, the photograph above may show a woman, but it is layered with so many visual queues. The first one is the torn-off wallpaper, which portrays how the Civil War in Lebanon has destroyed not only homes but also the dreams of the young people. The next layer is the little sketch on the right, which showcases a girl cycling upward. However, due to the image being cropped from the side, we really don’t know where she will end up, akin to the situation of many women who leave the country for a safe haven, just like Rania did. Last but not least is the woman who turned away from the little girl. Her somber expression makes us wonder: does she miss her childhood? This is why stories of Middle Eastern women photographers are so important to learn.

My work addresses the states of ‘Becoming’ – the fraught beauty and the vulnerability of growing up – in the context of the visceral relationships to our physical environment and universal humanity, but it is also about collaboration, experimentation, performance, empowerment, and about pushing the limits of creativity and self-expression ‐ both for the young women and for myself.

Tasneem AlSultan

Born in 1985, Tasneem left her teaching career to pursue photography in 2013. Her first breakthrough came in 2015 with her series, Saudi Tales of Love, which portrays marriage, divorce, and widowhood in Saudi Arabia. Since then, she has worked consistently to depict the region, especially the lives of women from various socio-economic backgrounds. Her other project, Maid in Saudi Arabia, was created following an incident in her own life. At the age of 9, Tasneem was instantly asked to avoid speaking to her live-in maid, who was 19 at that time. So when she found her voice, she decided to document those who do not come from such a privileged background.

The image above is a clear example of what it means to be house help. Their identities often go unnoticed, and they spend daily looking for a family while missing their own. The reflection helps to make the picture more engaging, while the deep blacks help to evoke a sense of sadness. The woman’s concealed face helps to add to the mystery of the story: who is she? Where does she come from? What is her education like? Where is her family? The white dress, which perhaps belongs to a kid, also makes one wonder whether the woman in the image is a mother herself. Overall, the picture, which shows the subject with dignity, also raises questions whose answers we may never know. This is exactly why having Middle Eastern women photographers showcase such stories is of utmost importance.

In her interview, Tasneem said:

Portraits or documentary, I hoped to photograph everyone in a natural setting. Not many household owners agreed to be included, so I didn’t pursue them. The only difficulty was that everyone photographed felt uncomfortable having me photograph their bedrooms. I didn’t want anyone to feel like I was invading their small private sanctuary, so I only photographed their bedrooms if invited in.

Tamara Hijazi

Tamara was 9 when she began making images with her point-and-shoot camera and explored the mountains of Palestine. Since then, her goal has been documenting her relationship to the land and its people. “Photography transformed from a way to just capture everything on camera to a dedicated medium for me to understand all these new feelings I was going through,” she said. In 2020, during the lockdown, Tamara began her series 2020-We Didn’t Know, which captures the fleeting moments the photographers saw during the pandemic.

The image above is the quintessential example of what the pandemic meant to most of us. With nowhere to go and nothing to do, we often turned to cooking. As many restaurants shut down, cooking was not only a means to eat better but also to express ourselves and tap into our roots. The recipe book in the frame adds more context. It showcases that the person making the Palestinian dish is following a recipe that may have been passed down from generation to generation. The slow shutter adds to the fleeting nature of our memories, which can easily slip from our minds during the monotony of daily life.

In our interview, Tamara said:

The only thing that gave me relief was documenting all of the moments I felt most settled in a time that was so unsettling. Like sitting with my two cats on a soft, glowing Sunday morning reading a book about herbal medicine or seeing the faintest hint of a double rainbow over the Chicago sky after a torrential rainstorm in July. The entire series is a tribute to the process of connection, disconnection, and reconnection over the height of the pandemic––with myself and my partner, with my family, with the landscape, with the empty streets of my neighborhood.

Nina Osoria Ahmadi

Nina is an Afro-Cuban and Iranian American photographer whose main focus is self-portraits. When she began photography in 2020, Nina wanted to embrace her mixed cultural identity, heritage, and sexuality. In her series, Come Be With Me, Nina uses her self-portraits as a means to understand herself and her identity. “I find that entering a place of self-reflection and imagining our own worlds is a great way to process pain and find the strength to take action toward better for ourselves and our communities,” she said.

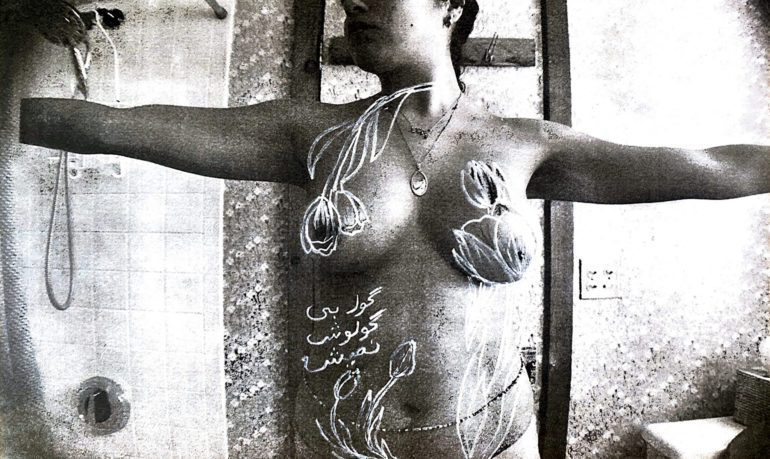

In that regard, her photographs make up our list of Middle Eastern women photographers, as her work stands at the intersection of political, social, gender, and cultural crossroads. In the image above, the nude self-portraits not only focus on body positivity but also highlight how often women’s bodies are controlled through a patriarchal system. The flowers and Arabic scripture appear to be added to make the image stand out. It also highlights her relationship with nature, Mother Earth, and her culture. Had the drawings were not included, the impact of the message would have been different.

In our interview, Nina said:

As in my earlier work, my understanding of my sexuality plays into these cultural conflicts, especially as I grow older into more complex understandings of gender in the context of my Persian and Cuban family – both cultures with extremely fraught histories of sex and gender politics. These works are not meant to stand as representative of the mass of artwork that hails from brown people or members of the African diaspora. This series is my exploration of personal experiences involving identity. I find that artists of color are often asked to stand as representatives for entire identity groups and cultural backgrounds, while white artists are not met with the preconception that their work examines entires ethnic or racial groups.

Mahnoosh Niakan

An Iranian photographer based in Berlin, Mahnoosh’s work is an example of what happens when tech meets art. Her photographs, often created using analog and digital cameras, oscillate between awe and wonder. Unlike the other photographers on the Middle Eastern women photographers list, Mahnoosh’s work is purely about depicting how she feels, using her emotions as the basis of the pictures. And sometimes, they can be political. The image above is an example of that. The Persian rugs and the traditional cap giveaways her identity, while the man posing flirtily in a robe with heels and makeup, is everything the country is against. The use of light, the colors, and the juxtaposition of Iranian culture are quite evident. A portrait like this will ruffle many feathers but also lead one to ponder over the message. Had a woman modeled for Mahnoosh, the message would have been slightly different.

In her interview, Mahnoosh said:

I find inspiration in every art form to create interesting sets or guide my subjects to achieve specific poses. I pay close attention to light design in old paintings and theatrical performances, as they greatly influence my approach to lighting in photography.