Some of the most distinct photographs of the medium were created during the Victorian era. From spirit photography to cyanotypes, from carte de visite to memento mori, the range of image-making was diverse as it was intense, akin to stars under the night sky. However, men were often at the forefront in those days, while women could only showcase their talent if they had someone to teach them. For instance, after obtaining guidance from William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins made the first photobook in the world. Like her, Julia Margaret Cameron is another woman, the pioneer of fine-art portraits, whose photographs have left an indelible mark on the medium.

The lead image is a screenshot of Burman Rare Books’ webpage.

A Late Bloomer And A Visionary

Julia Margaret Cameron began photography in 1863—at 48—when her daughter and son-in-law gifted her a camera. At the time, her husband was in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), her sons were at the boarding school, and their only daughter was married far away. Thus, the device was supposed to support her during her moments of solitude at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight.

Born in 1815, Cameron was a well-read woman with an even more eccentric circle of friends and neighbors. For instance, she knew and corresponded with painter G. F. Watts, poets Robert Browning, Henry Taylor, and Alfred Lord Tennyson, scientists Charles Darwin and Sir John Herschel, and the historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle. In fact, Herschel became her close confidant during her photographic journey. Back then, little did the two know that Cameron’s way of seeing would influence the medium.

I believe that… my first successes in my out-of-focus pictures were a fluke. That is to say, that when focusing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon…

Julia Margaret Cameron

When Cameron first started making photographs, it was an arduous process. She had a large wooden camera, which was cumbersome to use. At that time, one had to produce albumen prints from wet collodion glass negatives, which meant she would work with a 12 x 10-inch glass plate. It is then covered with photosensitive chemicals in a darkroom, which is exposed to the camera when damp. In the darkroom, the glass plate was developed. Cameron had to place sensitized photographic paper directly on the glass to make the prints and then reveal it to sunlight.

“I began with no knowledge of the art,” she once wrote about a blunder. “I did not know where to place my dark box, how to focus my sitter, and in my first picture, I effaced to my consternation by rubbing my hand over the filmy side of the glass.” However, that did not deter her. Despite being an amateur, Cameron was confident that what she offered was something special. As a result, she took extra steps to protect her copyright and promote her works through exhibitions, marketing, and publishing. She sold 80 prints to the Victoria and Albert Museum when she acquired a camera. Although she had no inclination towards commercial photography, she managed to set up a studio, a great feat at that time.

A Photographer’s Photographer

Since Julia Margaret Cameron was not making her portraits to sell them, her sitters were her friends, relatives, house staff, and more. As an amateur, she enjoyed the theatrics of her portraits, where she would use natural elements to delve into qualities of innocence, integrity, knowledge, or purity. However, many of her portraits were created from her religious beliefs, readings, and the scenes of fifteenth-century Italian painting. For instance, her maid posed as the Madonna, while her husband became Merlin and a child of her neighbor’s infant Christ.

My aspirations are to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real and ideal and sacrificing nothing of the truth by all possible devotion to poetry and beauty.

Julia Margaret Cameron

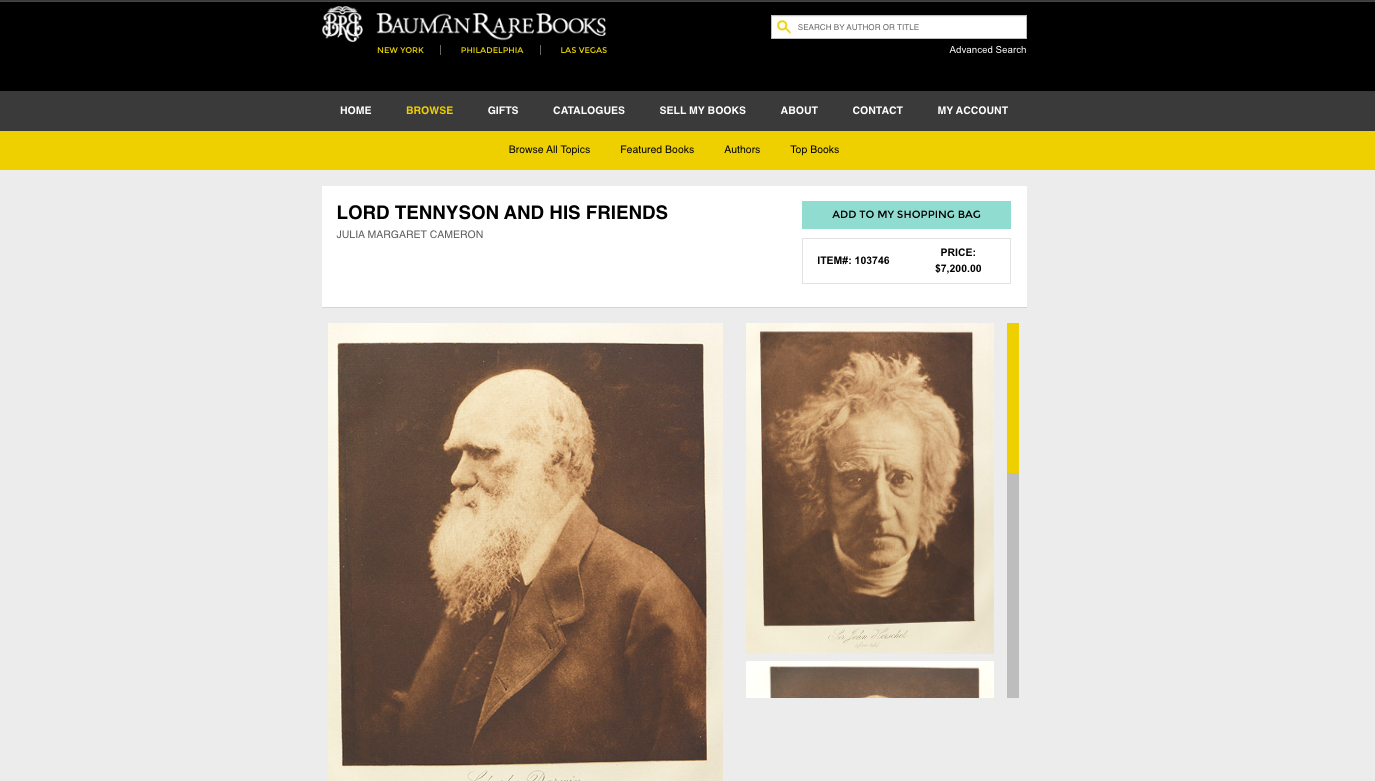

While her artistic portraits were elaborate, her photographs of scientific figures were particularly striking for their adoration of the subjects and realism. For instance, the portraits of Sir John Herschel, a renowned scientist and photographer, and Lord Tennyson are some of the most well-known images in her oeuvre. The use of soft focus made her pictures stand out, a characteristic that was not popular then. Moreover, the long exposure and moody natural light gave her images a dream-like quality, too. Unlike the images of women, the portraits of the luminaries had a distinct style. Cameron captured their likeness and conveyed their emotional state and intellect. In Herschel’s photograph, for instance, his unkempt hair, the lines on his face, and the grave expression portray his dedication to science.

However, despite having a unique style and the fervor to try something different, Julia Margret Cameron’s work was not always admired. “In these pictures, all that is good in photography has been neglected, and the shortcomings of the art are prominently exhibited. We are sorry to have to speak severely about the works of a lady. Still, we feel compelled to do so in the interest of the art,” said a reviewer about her exhibit in The Photographic Journal. But some stood by her. For instance, the Illustrated London News wrote that her portraits are “the nearest approach to art, or rather the most bold and successful applications of the principles of fine-art to photography.” As it is with any photographer, Cameron didn’t think much of the naysayers, expressing that it would have discouraged her efforts if she had “not valued that criticism at its worth.”

When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavored to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer.

Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron passed away in 1879; however, her work continued to shape the medium long after. Alfred Stieglitz advocated her artistic vision and exhibited her work alongside his during his time. In 1893, her son, Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, revived her portraits as a publication, Lord Tennyson and His Friends, which featured 26 photogravures made from her original negatives. In the 900 photographs she took, Cameron demonstrated her status as one of the pioneers of fine art photography who succeeded in capturing the beauty of a bygone era.

Julia Margaret Cameron’s Lord Tennyson and His Friends is now available for purchase at Burman Rare Book’s website.