The beauty of photography is that we get to relive the ‘firsts’ and important images of an event that will alter and change our history over and over. The photographs captured by Philae, the lander of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta mission, is an example of that. A decade ago, on November 12, the ESA achieved the impossible; Philae became the first ever human-made object to safely and successfully land on a comet. Since November is already here, this marks the 10th anniversary of our victory as a species, and here’s a look back at the significant event and the images that helped us shine brighter since then.

All images in the article are courtesy of ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA.

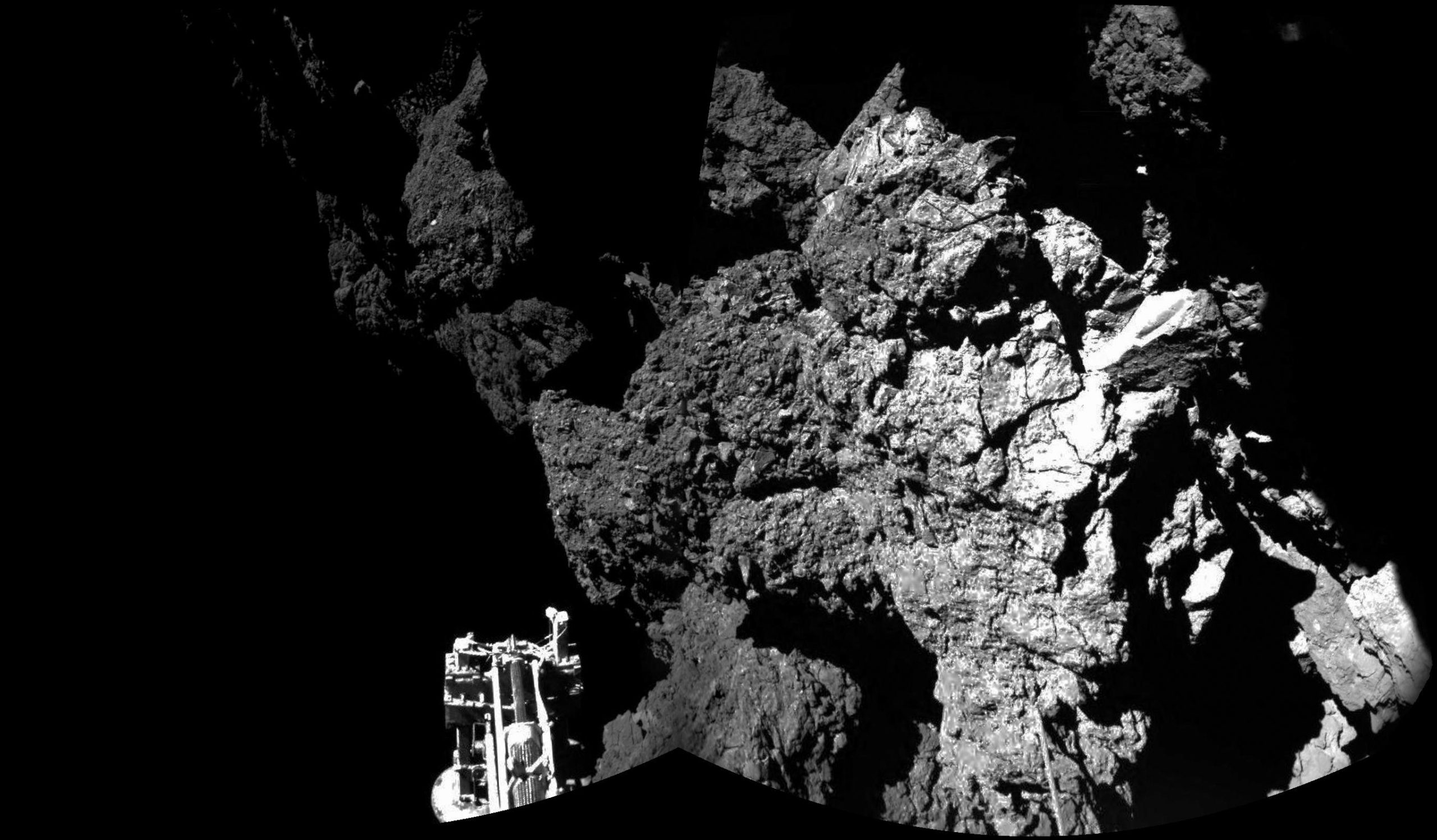

The year was 2004 when ESA decided to take on a challenging mission to capture photographs of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko that would help scientists and researchers with insights into how our solar system was built. The photograph is a result of that successful journey, which showcases Rosetta, a spacecraft, with lander Philae on the comet, where one of three feet of the lander is visible in the foreground of the image. While the image was captured on November 12, 2014, the actual work began all the way in March 2004, when Rosetta was sent to the comet. The spacecraft traveled 6.4 billion kilometers for a decade, only to grow closer to Comet 67P on August 6, 2014

One of the challenges it faced was finding a landing spot that would be ideal for Philae. As the scientists raced against time, they finally found a place after looking at the images sent by Rosetta. The group chose a spot near the lobes of the comet, which was called Agilkia. After a few challenges in the landing, Philae was separated from the spacecraft and began its hours-long descent. However, due to the issues with the terrain, the lander had to contact the ground four times. In the first attempt, it went airborne, and the more times it did so, it gave science a unique opportunity to capture images and data of the comet. At one point, it even grazed by a cliff of the comet, and soon, the science learned that its density was that of frothy cappuccino foam. Later, they discovered the comet’s makeup was closer to a blend of dust and ice.

As part of its instrument, ESA also included Comet Nucleus Imaging and Spectroscopy Experiment (CIVA) cameras, which were critical in capturing the most iconic and important images from the comet. It took the lander 57 hours to finally make a touchdown, after which the lander captured the first image of a human-made object on a comet’s surface. The picture is a detailed view of the Solar System’s archaic relic. In many ways, the images and the mission brought together the mysteries of the solar system a step closer to unraveling it. For instance, Philae was also responsible for taking the first seismic measurements of a comet since the Apollo 17 mission to the Moon in 1972. It measured its temperature and examined the gases, revealing previously unknown components.

After this excursion, the lander’s battery died, and Philae was located again after only a year. Rosetta, the spacecraft, continued to send back the data until 2016. This successful mission gave the scientists the direction to look further at the origin of life in space. Today, ESA is continuing to work on various Comet Interceptor missions, which will be launched over the next few years. And, of course, the images that we will receive later will not only contribute to unraveling the mysteries of the universe but also continue to remind us why photography remains one of the most important inventions of all time.